The Lycoming County Historical Society held its Annual Meeting on Saturday. We were honored to present the Student Historian Award, as well as honor the Lycoming County Women’s History Collection as Volunteer of the Year. We also presented heart-felt “Thank You’s” to outgoing board members and enjoyed a presentation by William E. Nichols, Sr. Below are some highlights from the wonderful evening.

The Lycoming County Historical Society held its Annual Meeting on Saturday. We were honored to present the Student Historian Award, as well as honor the Lycoming County Women’s History Collection as Volunteer of the Year. We also presented heart-felt “Thank You’s” to outgoing board members and enjoyed a presentation by William E. Nichols, Sr. Below are some highlights from the wonderful evening.

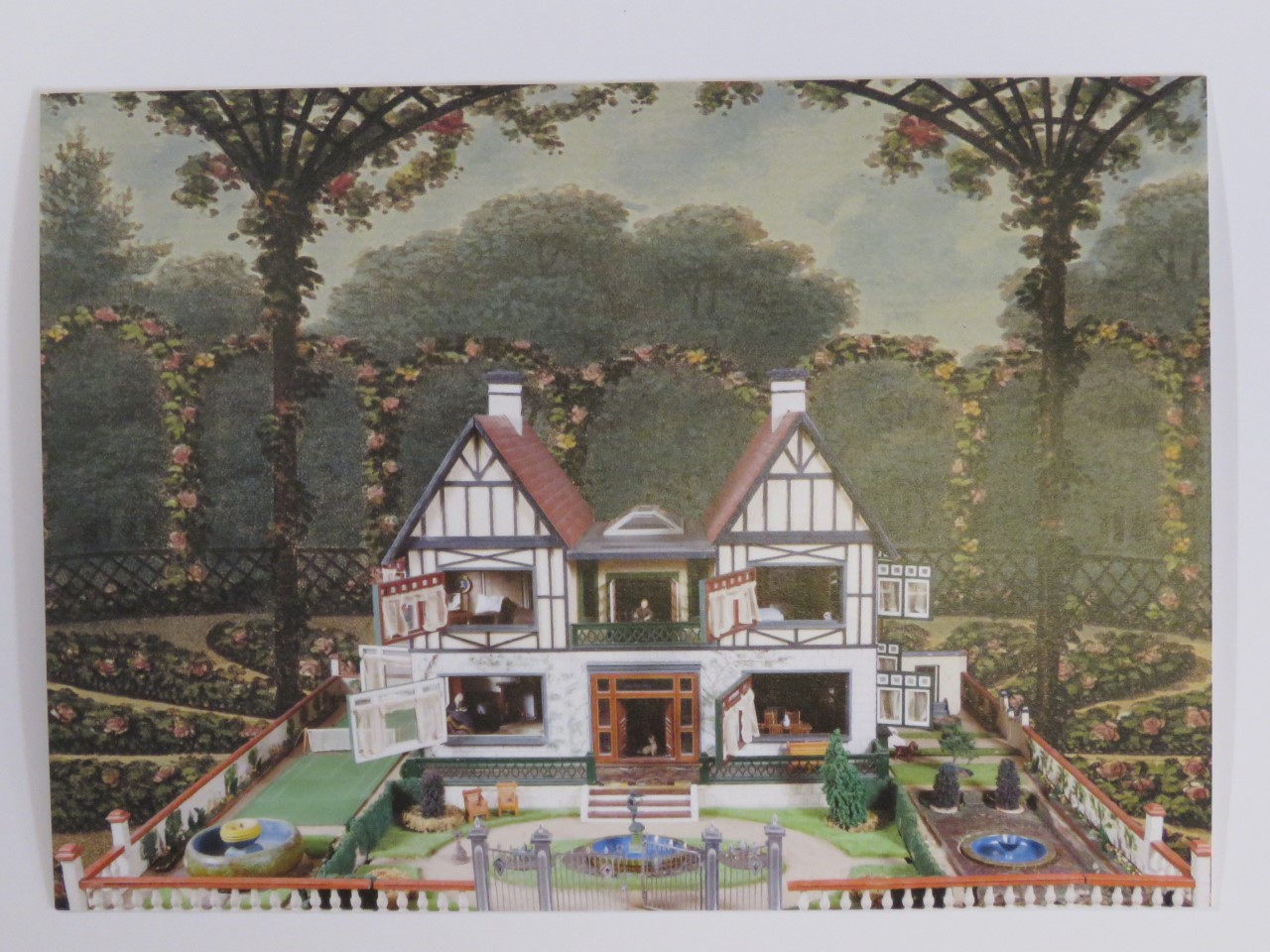

A Student Historian Award was presented to Anna Lee Hafer for her essay concerning an object within the museum. She chose to write on the Manor Hall Dollhouse. She is a student at Williamsport Area High School. A number of students responded to the LCHS essay contest, choosing items within the museum and placing them within the relevancy of today. Students chose to write about the following objects/areas of the museum included: a Corona typewriter, the canal system of Pennsylvania, the blacksmith shop, the Greek Revival Parlor, the One-Roomed Schoolhouse, and the telephone in our General Store.

Anna’s essay, "Living in the Past" follows below

More highlights from the evening. Outgoing Board member Gina Campana receiving a certificate of appreciation from newly-elected Board President Chuck Luppert and Director Gary Parks:

Director Gary Parks presented outgoing Board President John Raymond with a certificate of appreciation:

William E. Nichols, Sr. speaking on “The History of Our Valley and the Williamsport Municipal Water Authority”:

Director Gary Parks presenting the Volunteer of the Year Award to representatives of the Lycoming County Women’s History Collection Committee; from left: Helen Yoas, Alison Gregory, Janet Hurlbert:

Living in the Past: The Manor Hall House

It caught my eye as soon as I entered the Thomas T. Taber Museum: an elaborate but tiny house circa 1930 with the intricate details of an artist. This mahogany-and English-oak home contained hundreds of individual pieces. Miniature people peered their heads at me from around every corner: a maid washing dinner dishes in the kitchen, a grandmother finishing her favorite book in the drawing room, a lady enjoying the sunset from the balcony. What impressed me the most about the Manor Hall House was the detail Reverend H. Mowbray-Finnis, builder and headmaster of the co-educational school in New Zealand, incorporated into the home, along with the careful attention given to it by Ruse Gross, the woman who bought and refurbished it after his death. The amazing craftsmanship has made the Manor Hall House into a home for the wooden figures that live there: teeny playing cards littered the nursery, little candlesticks decorated the dining room table, and a tiny white dog welcomed visitors into the building. I could almost hear him barking his “hello.” Such details bid me enter not only into this lovely Tudor dwelling, but also into the past.

It caught my eye as soon as I entered the Thomas T. Taber Museum: an elaborate but tiny house circa 1930 with the intricate details of an artist. This mahogany-and English-oak home contained hundreds of individual pieces. Miniature people peered their heads at me from around every corner: a maid washing dinner dishes in the kitchen, a grandmother finishing her favorite book in the drawing room, a lady enjoying the sunset from the balcony. What impressed me the most about the Manor Hall House was the detail Reverend H. Mowbray-Finnis, builder and headmaster of the co-educational school in New Zealand, incorporated into the home, along with the careful attention given to it by Ruse Gross, the woman who bought and refurbished it after his death. The amazing craftsmanship has made the Manor Hall House into a home for the wooden figures that live there: teeny playing cards littered the nursery, little candlesticks decorated the dining room table, and a tiny white dog welcomed visitors into the building. I could almost hear him barking his “hello.” Such details bid me enter not only into this lovely Tudor dwelling, but also into the past.

The Manor Hall House was constructed in such a way that I could look straight into each room and thus into the lives of both the people who lived there and those who were employed by the family. Most of the rooms in the home have parquet floors and glass windows. According to The Williamsport Sun Gazette’s article entitled “Museum acquires historical dollhouse” (2012), the library is paneled in English oak, and the drawing room is half paneled in mahogany. The central hall is complete with over two thousand pieces of mahogany; the entire home even has running water and electricity! The kitchen, located in the front of the home, has aqua-blue-and-white-checkered tiles on the walls and a geometric mosaic floor constructed out of wood. The kitchen cabinets even match the kitchen tiling perfectly. Some of the rooms appear to have wallpaper, and the nursery has tiny paintings that each tell a story. One of the paintings depicts cartoon mice all dressed up for a day on the town, swinging back and forth on enormous plants, and the little ones chase each other around the seemingly giant violet flowers while larger-than-life butterflies circle around them. The house truly seems like a home.

Because of its features, the Manor Hall House was displayed worldwide to raise money for children’s hospitals. According to the Lock Haven Express’ article “The Manor Hall House,” the toy was built in New Zealand and exhibited throughout England in various department stores. Later, it was displayed in London where Queen Elizabeth II (then Princess Elizabeth) and her sister Margaret traveled to see this masterpiece (“The Manor Hall House”). It was finally auctioned in New York before coming to the Thomas T. Taber Museum.

Unlike other dollhouses at the time, the Manor Hall House was made with intricate detail and real wood (“The Manor Hall House”). According to A History of Dollhouses and Furnishings 1890 to 1990 by Jennifer McKendry, other dollhouses were made of plywood, fiberboard, and cardboard and covered with colorful printed papers. Along with commercially made products, there were also a great deal of dollhouses and furniture handmade out of cheap materials (McKendry).

The Manor Hall House is Tudor architecture, a late Medieval and early Renaissance style, which began with the first part of the reign of the Tudor Monarchs (Britannica). According to the Wentworth Studio web site, the Tudor style is characterized by large rectangular and/or bay windows, complex roofs, embellished doorways, and elaborate chimneys. This style of homes was built for the wealthy, most of whom had made money off the 1920s stock market (Wentworth Studio). According to Barbara C. Barette, the Tudor style—with its defining straight lines, dark timber, and a great central hall—fits the Manor Hall House perfectly. The origin of Tudor style buildings in medieval Britain most probably led to the growing popularity of this architecture (Wentworth Studio). Dollhouse designs were based on what the middle-class families viewed as “beautiful,” and thus such dollhouses were soon manufactured and sold worldwide. The Tudor style flourished in popularity during the 1930s, and innovative marketing helped make it popular in America as well. According to “Antique Home Style,” the Tudor style remained prevalent in American homes for around 50 years.

The Manor Hall House told me a great deal about the class system in the past. It is obvious from its large size and beautifully tended landscape that a wealthy family would have owned the home. Tennis courts flank the left side of the building. The family was also wealthy enough to employ maids, and this shows the clearly different lives these two classes lived.

This Manor Hall dollhouse differs from its modern counterpart; there is a clear difference between the lives of the homeowners and the live-in nursery maid who cleans the home and helps with the children. In modern dollhouses, it is common to only see a mother, father, daughter, and son, not maids and workers. Modern dollhouses often depict the middle-to-upper class since this is what many children find attractive. Some dollhouses today also are geared toward girls rather than simply depicting a specific style of house. For example, many offer mostly pink rooms and decorations, which differ from the less gender-specific furnishings and interiors of the 1930’s.

In addition, some twentieth-century dollhouses include the newest features and gadgets and offer a design that allows the child to see into the rooms of the house. The dollhouses mass-produced today—as well as such accessories as TVs, minivans, and pets—are typically made of plastic and safe for children, an important concern for modern parents. While during the 1930’s dollhouses were a family event, with fathers and members of the family handcrafting furniture for the homes, this is not typical with today’s busy schedules.

Dollhouses have also decreased in popularity; new technological gadgets often replace a toy that has existed for many decades. Nevertheless, many electronic living and decorating games exist on-line, such as Neopets, Webkins, Dollhouse Suburban Estate, and Roominate, where you can decorate a house, “play” with its occupants, and even learn about science. Minecraft, which is popular with girls but even more popular with boys, allows you to create, build, and decorate entire communities. In the future, electronic dollhouses and “virtual world” games such as these will only become more elaborate.

Just as the dollhouses of the 1930s and contemporary dollhouses reflect societal values and class systems, so, too, will dollhouses of the future. For instance, perhaps we will see dollhouses modeled after ecological homes, complete with solar power and plant ecosystems to better conserve energy, food, water, and materials. Perhaps a car-charging station will be standard, and a network of social media obvious. Maybe dollhouses instead of coming with a mother, father, daughter, son, and pet will also come with a robot!

Yet, despite all these changes, there’s something about a dollhouse—no matter the century—that draws us into its tiny world. It reflects back part of our lives. It makes us yearn for that “home sweet home” that maybe, just maybe, we may glimpse inside its mahogany or plastic or solar-powered walls.